In Search of the Echoes of History— Strangers in the Land: An Open Letter to Future Chinese Americans

在“异乡”寻找历史回声 ---《异乡人》:写给未来的华裔子孙的公开信

By Ma Siwei (马四维)

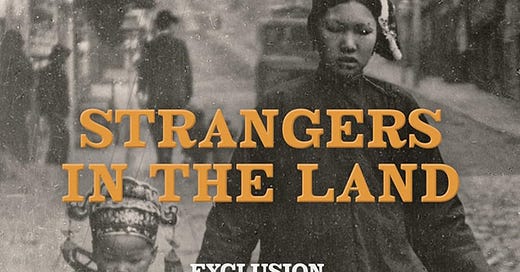

In 2025, Michael Luo, executive editor of The New Yorker, published a remarkable book—Strangers in the Land: Exclusion, Belonging, and the Epic Story of Chinese Americans (《异乡人:排斥、归属与美国华裔的史诗故事》). The genesis of the book was a personal moment of racial hostility. In 2016, Luo was accosted on a New York City street and told to “go back to China.” The encounter shocked him. That shock catalyzed a multi-year archival journey, during which Luo came to recognize how little he knew of Chinese American history. It compelled him to interrogate his own identity—as a second-generation Chinese American with a prestigious education and a secure professional role—and to undertake the writing of this vivid and forceful historical narrative.

Written in lucid prose and guided by a journalist’s instinct for investigation, Strangers in the Land reconstructs over a century of Chinese American “foreignness”—a memoryscape of struggle and marginalization dating back to the mid-19th century. The book does more than fill a void in mainstream American historiography. It offers second- and third-generation Chinese Americans a map of ethnic self-understanding, grounded in historical experience.

Institutionalized Discrimination and the Dark Chapters of American Law

As a work of narrative history, the book’s most vital contribution is its unflinching portrayal of episodes long omitted from the dominant American storyline. Luo assembles a systematic account of anti-Chinese hostility from the 1850s onward, when tens of thousands of Chinese laborers crossed the Pacific in pursuit of gold and railroad jobs—only to become scapegoats amid waves of white unemployment.

Luo recounts in detail the 1871 Chinese Massacre in Los Angeles, in which seventeen Chinese men were lynched; the forced expulsions of Chinese communities in Tacoma, Seattle, and other cities at the century’s end; and, most significantly, the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Of particular note is his documentation of how nearly 200 towns across the American West, at different moments in history, enacted systematic measures to drive out or bar Chinese residents—many of these acts largely unknown or underreported until now.

Yet Strangers in the Land is not only a chronicle of incidents—it is also a record of individual lives. Luo writes movingly of Gene Tong, a Chinese herbalist who was lynched in Los Angeles, and of Wong Kim Ark (黄金德), who fought a landmark legal battle for birthright citizenship and whose case became central to the application of the Fourteenth Amendment. These personal narratives coalesce into a larger arc: how a people once cast out came—slowly, painfully—to claim a place in the nation.

The book makes clear that anti-Chinese violence was not merely the product of popular prejudice—it was the result of legally sanctioned, institutionalized exclusion. The 1870 Naturalization Act extended citizenship to people of African descent but explicitly denied it to Asians. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was the first federal law to restrict immigration based on race. Over the following decades, the legal scaffolding only grew more punitive: Chinese immigrants were denied naturalization, barred from entering the country, and rendered what we might now call the prototype of the “illegal immigrant.”

Luo argues that the United States, beginning with its exclusion of Chinese, pioneered a legal regime that defined citizenship eligibility along racial lines—one that endured until 1943, when the exigencies of World War II finally forced its repeal. This history represents not only a refutation of American ideals of liberty, but a stark illustration of how democratic institutions can capitulate to ethnic hatred under political pressure.

Drawing on meticulous archival research and sharp narrative sensibility, Luo makes an urgent point: the legitimacy of a democracy lies not in the will of the majority but in its capacity to protect the dignity and rights of its most vulnerable. In the America of that era, few groups were as thoroughly dispossessed as the Chinese.

A Mirror for Today’s Anti-Immigrant Resurgence

But Strangers in the Land does not stop at recounting the past—it confronts the present. In recent years, the United States has witnessed a reawakening of anti-immigrant sentiment. From the Trump administration’s “Muslim ban” and restrictions on Chinese visas, to the surge of Sinophobic rhetoric during the COVID-19 pandemic—epitomized by the phrase “Chinese virus”—and the more recent questioning of Asian Americans’ loyalty by political figures, xenophobia and racial mistrust have once again entered the bloodstream of electoral discourse and social media.

Polls conducted by Axios and Pew Research reveal that more than one in four American adults believe Chinese Americans are more loyal to China than to the U.S. Meanwhile, 63% of Asian Americans report feeling unsafe in some aspect of their daily lives. These statistics are chilling, and they validate the book’s underlying message: the history it recounts is not past, but present. Today’s suspicion, surveillance, and rejection of Chinese Americans are the modern reverberations of the “stranger” label branded onto them in the 19th century. As Luo writes in the closing pages, “We think history has ended—but it is merely waiting for its next occasion.”

The power of Strangers in the Land also stems from Luo’s own position. As an executive editor at The New Yorker, he commands a rare platform within America’s media establishment. His voice carries the weight of both authority and access. The very act of writing this book represents a reorientation of Chinese American identity within mainstream American culture.

More than a historical account, the book becomes a meditation on personal identity. Luo confesses that before embarking on the project, he too had been a “bystander to history.” Over the course of writing, he became instead its inheritor and teller. This evolution mirrors the experience of many second- and third-generation Chinese Americans: raised within dominant cultural frameworks, yet awakening in adulthood to the burdens—and responsibilities—of ethnic lineage.

This shift in consciousness has broad implications for Asian American identity. In an era when race and diversity occupy center stage in public life, Chinese Americans in mainstream society must no longer be mere models of assimilation. They must become historians, narrators, and political actors.

Strangers in the Land is not merely a history book—it is an open letter to the descendants of Chinese America. It insists that Chinese American history is not peripheral, but central to the drama of American democracy and exclusion. Those who were expelled, humiliated, or silenced were also those who, through persistence, litigation, speech, and action, infused American society with deeper reflections on rights, belonging, and the meaning of humanity.

For young Chinese Americans today, the book offers more than knowledge—it offers reason for action and a compass for self-definition. In this land we call “foreign,” we are no longer merely the defined. We are now the definers.

The book’s title, Strangers in the Land, does not simply describe a condition. It summons resistance to it. May we be, no longer, strangers—but Americans who leave a trace of our lineage on this land.