Universities Are Facing an “Admissions Shortfall,” and Far-Reaching Consequences Lie Ahead

大学开始出现“招生荒”,后面还有连锁反应......

Authored by Bu Yu (布语)

【Editor’s Note: In 2024, China’s universities, particularly private institutions, faced an unprecedented “enrollment shortfall” despite record-high Gaokao participation. Private colleges that once thrived are now struggling to attract students, even in popular majors. In Guangdong, schools like Zhanjiang University of Science and Technology experienced severe deficits, reflecting a nationwide trend. Simultaneously, vocational schools and junior colleges are growing in appeal, even attracting high-achieving students due to their lower costs and high employment rates. The oversupply of bachelor’s degree holders has diminished its value in the job market, with graduates facing tougher competition than associate degree holders. Structural imbalances and misaligned expectations, termed “degree mismatch,” have left advanced degree holders underemployed. Vocational institutions, offering practical skills and competitive employment outcomes, have become a key option for many. This shift highlights the need for adaptability in educational and career planning as an evolving job market demands reshape traditional paths to success.】

2024 saw a curious new development: While the number of students taking the national college entrance exam (Gaokao) reached an all-time high, universities began reporting an “enrollment shortfall.” This trend hit private institutions especially hard—even those offering bachelor’s degrees found themselves severely lacking applicants.

At the same time, many high-achieving students were scrambling to enroll in vocational schools. Times have changed. With private undergraduate programs gradually abandoned and universities struggling to fill their incoming classes, a vast domino effect has begun, poised to influence the destinies of countless individuals. Everyone involved would do well to prepare.

In Guangdong Province (广东), China’s largest provincial economy—where Gaokao numbers rank among the country’s highest—schools like Guangzhou College of Commerce (广州工商学院), Zhanjiang University of Science and Technology (湛江科技学院), and Guangdong Polytechnic College (广东理工学院) all experienced massive enrollment deficits, remaining undersubscribed even after multiple rounds of recruitment. Zhanjiang University of Science and Technology alone reported a record shortfall of over two thousand students.

Not long ago, some of these private schools were “hot tickets” for parents. Now, they find themselves summarily “discarded.”

Guangdong Polytechnic College (广东理工学院) planned to enroll 5,318 students in the province; on the first pass, they only drew 2,989, leaving 2,329 spots unfilled—a 56.2% placement rate.

Guangzhou College of Commerce (广州工商学院) aimed for 5,071, but the first-round count was 3,950, leaving 1,121 unfilled—a 77.9% placement rate.

Zhanjiang University of Science and Technology (湛江科技学院) planned to admit 6,866 students (general undergraduate category) but received only 2,718 first-round applicants, creating a 4,148—student gap and a placement rate under 40%.

The blow came abruptly. Over the previous three years (2021–2023), the minimum acceptance ranking for the History track at Zhanjiang University of Science and Technology had ranged between approximately 82,142 and 100,700. This year, despite a stable admissions quota and a larger test-taking population, that minimum ranking plummeted to 108,667. Evidently, the turning point in today’s educational environment has arrived with stunning force.

Nor is this phenomenon limited to Guangdong. Across the country, private undergraduate colleges are suffering from a similar chill. Even in Shandong Province (山东)—renowned for producing hordes of public-service aspirants and home to many students holding a strong commitment to bachelor’s degrees—the first round of regular admissions for ordinary undergraduates left over 7,000 unfilled slots. A tally shows that 12 colleges had more than 100 vacancies each—virtually unthinkable in earlier years:

Weifang Science and Technology College (潍坊科技学院): 163 spots left

Shandong Yingcai University (山东英才学院): 282 left

Weifang Institute of Technology (潍坊理工学院): 303 left

Qingdao Hengxing University of Science and Technology (青岛恒星科技学院): 310 left

Qingdao Institute of Technology (青岛工学院): 427 left

Qingdao Huanghai College (青岛黄海学院): 431 left

Shandong Xiehe University (山东协和学院): 473 left

Qingdao City University (青岛城市学院): 485 left

Qilu Institute of Technology (齐鲁理工学院): 572 left

Yantai Institute of Technology (烟台理工学院): 682 left

Qingdao Binhai University (青岛滨海学院): 694 left

Shandong Huayu University of Technology (山东华宇工学院): 936 left

Every one of these undersubscribed institutions is privately operated, an awkward reality indeed. On a national scale, many schools remain heavily under-enrolled even in the second round of supplementary admissions, forcing them to lower the minimum score threshold.

For instance, in Hunan Province (湖南), where the 2024 baseline for undergrad admissions (Physics track) was 422 points, plenty of private universities found themselves accepting students below that line, even after the second round of recruitment:

Capital Normal University Kede College (首都师范大学科德学院): 408 points

Haikou University of Economics (海口经济学院): 405 points

Hunan Information Institute (湖南信息学院): 405 points

Hunan International Economics University (湖南涉外经济学院): 402 points

A gap of around 20 points below the cutoff might once have seemed enticing, but this year, many applicants are feeling deflated. Meanwhile, Baoding Institute of Technology (保定理工学院) in Hebei Province (河北) entered its second round of admissions with 287 available seats in the History track and 506 in the Physics track.

Nor are these vacancies confined to unglamorous majors—candidates are showing little interest in fields as traditionally popular as electrical engineering and automation, computer science and technology, and electronic information engineering.

Why are universities suddenly under-enrolled, and why are private undergraduate programs getting left behind?

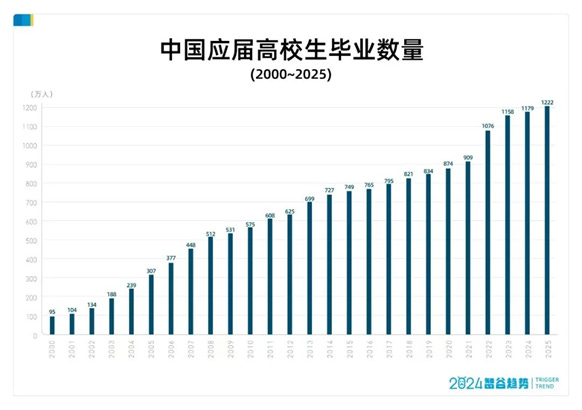

The chief explanation may be that the number of bachelor’s degree holders is already colossal. Official statistics show that in 2023, China’s gross higher education enrollment rate reached 60.2%, with over 47 million undergraduates currently in school. By 2025, the country’s college graduates are projected to number 12.22 million—a new record on top of those broken year after year. Compared to 2005’s 3.07 million, that figure has essentially tripled.

In the past, employers snapped up anyone with a bachelor’s degree. Today, a bachelor’s degree is the market norm—no longer a prized rarity. In fact, the job market has inverted in surprising ways: master’s and doctoral graduates struggle more than undergraduates, and undergraduates fare worse than those with associate degrees.

According to Zhilian Recruitment’s College Graduate Employment Survey Report (《大学生就业力调研报告》), only 44.4% of new master/doctoral graduates for 2024 had secured job offers, while undergraduate offers stood at 45.4%. Those with two- or three-year associate degrees boasted the highest offer rate, at 56.6%. This unprecedented “inverse” pattern arises from a structural imbalance in employment: more and more highly educated graduates chase a limited pool of positions requiring advanced degrees. The bulk of open jobs—whether the old “three guardians” of security guards, housekeepers, and cleaners or the modern wave of gig economy services like ride-hailing, food delivery, and drone operation—do not mandate a bachelor’s credential.

Inevitably, the era that saw private undergraduate programs flourishing or expanding heedlessly has reached a turning point. After 2010, private colleges enjoyed a near decade of “golden growth,” with public institutions eager to partner with social capital to found “independent colleges”—for example, Zhejiang University City College (浙江大学城市学院) and Jinling College of Nanjing University (南京大学金陵学院). Bearing the names of famous schools, these so-called “Tier Three” programs once thrived and saw their entrance requirements spike. Today, that clamor has receded. It’s not just students and parents turning away—private tutoring and admissions services have also changed tack.

Many such services now advise those who hover around the bachelor’s cutoff to enroll in public junior colleges, which are far cheaper than private four-year institutions. After all, public associate degree programs typically cost only a few thousand yuan per year, while private four-year schools may charge three or four times that amount. Furthermore, these private institutions often suffer from high tuition fees, thinly qualified faculty, and chaotic management—a bad reputation that advertising blitzes can no longer salvage.

“Poor environment, high fees, and bleak employment prospects” have become the succinct verdict undermining confidence in private colleges. As more people have unfortunate experiences, the pitfalls can no longer remain hidden. Looking ahead, the cooling trend for private undergraduates will be hard to reverse.

In striking contrast, junior colleges and vocational schools are growing ever more popular, to the point where some provinces are seeing high-scoring students vying for a spot at vocational institutions.

In Zhejiang Province (浙江), a female candidate from Hangzhou who scored 602 on the Gaokao—fully 110 points above the local undergraduate threshold—chose to attend Zhejiang University of Technology and Trades (浙江机电职业技术大学), enrolling in the Rail Transit Equipment and Control Technology program.

Why would she pick a vocational college despite being qualified for a “Double First-Class” (双一流) institution? In her own words, the school’s employment rate was impressively high—up to 98%. Changing patterns in the job market are subtly reshaping the decisions of over 13 million Gaokao applicants, making vocational schools a key option on many preference lists. Nationwide, it’s no longer uncommon for top scorers to enter two- or three-year colleges.

In Hunan Province (湖南), a total of 119 professional clusters at higher vocational institutions reached or exceeded the undergraduate admission mark in 2024—twice as many as last year’s 52. For example, among Hainan’s applicants to Changsha Social Work College (长沙民政职业技术学院), the top scorer this year reached 573—90 points above the local undergraduate line. In Hunan itself, the highest score was 485, and the lowest was 449, all above the province’s undergrad cutoff. On average, these students were 39 points above that line.

Simultaneously, many undergraduate institutions are reconfiguring their majors to align more closely with market demand. Meanwhile, some junior colleges are evolving into “vocational universities,” a best-of-both-worlds approach that confers an accredited bachelor’s diploma while offering specialized skills. Their diplomas hold the same legal standing as a regular bachelor’s degree.

One example is Civil Affairs Vocational University (民政职业大学), recently approved in 2023 to offer five four-year programs, including Modern Funeral Services Management and Marriage Services and Administration—both aiming to serve vital social needs. Many robust “hidden gem” junior colleges are likewise experiencing renewed popularity, and the number of vocational universities nationwide has grown to 51. In 2023, these institutions enrolled 89,900 students for bachelor-level vocational degrees, a 17.82% increase from the previous year—though still just 1.6% of total higher vocational enrollment. Compared to the average private undergraduate path, such vocational bachelor’s programs offer a compelling alternative.

The rapid pace of change can be disorienting. For an entire generation, adapting to these shifts often leaves little time for reflection. It’s become common for graduates—even those from “Double First-Class” universities—to return to technical schools for “re-education,” learning specialized skills to meet immediate market needs.

According to statistics from Guangdong Lingnan Institute of Technology (广东岭南职业技术学院), over the past two years, more than 150 bachelor’s degree holders have enrolled there to acquire new professional certifications. In essence, it’s an exercise in self-correction—a recognition and acceptance of the current reality.

This is both the best and the most challenging era. Only those who remain committed to continual learning and adaptability can truly keep pace. If you have friends or family navigating their own college choices, be sure to share this article with them. A clear-eyed understanding of the situation now could mean fewer detours down the road.

This translation is an independent yet well-intentioned effort by the China Thought Express editorial team to bridge ideas between the Chinese and English-speaking worlds. The original text is from Zhigu Qushi Trend (智谷趋势Trend), authored by Bu Yu (布语)

Kindly attribute the translation if referenced.